Colonial Williamsburg offers an immersive and meticulously researched window into life in early America. I have returned many times over the years, and each visit deepens my affection for this extraordinary place. I am delighted to share my Colonial Williamsburg travel guide with you and hope it inspires your own journey.

Colonial Williamsburg is the nation’s oldest and largest living history experience, and it remains close to my heart. There are moments when I feel as if I truly belong on Duke of Gloucester Street, moving through the city as it once stood when Williamsburg served as Virginia’s 18th century capital.

A mile-long historic corridor stretches from the 1693 Wren Building at the College of William & Mary to the reconstructed Capitol. This remarkable “Revolutionary City” encompasses 301 acres, including 88 original structuresand hundreds of carefully reconstructed houses, shops, public buildings, and gardens. Skilled tradespeople and costumed interpreters animate the streets, while ongoing research, archaeological digs, and restoration projects ensure the site is constantly evolving.

Visitors wander along car-free lanes or ride by horse-drawn carriage, pausing to watch artisans at their benches and merchants behind shop counters. The craftsmen truly practice their trades—producing goods for sale and items needed throughout Colonial Williamsburg. Guests also encounter the Nation Builders, actor-interpreters who portray influential figures from the city’s past.

These individuals represent real men and women—black and white, free and enslaved—whose lives shaped Williamsburg and the larger story of America. Many Nation Builders devote years to studying their historical counterparts, developing a deep understanding of their voices, choices, and experiences. Ask a question, and they reply in character, sometimes using documented quotations.

The chance to grasp our nation’s early struggles from the fight to break from British rule and the parallel struggle of those held in bondage—offers a powerful reason to visit. History may whisper in many places, but in Colonial Williamsburg, it speaks with clarity and conviction.

However, the destination offers far more than history. Colonial Williamsburg also makes an ideal girlfriend getaway, family vacation, romantic escape (after all, Virginia is for Lovers), and Baby Boomer retreat. Visitors discover a city with fine dining, world-class museums, resort-style lodging, heritage gardens, championship golf, soothing spas, and charming antique shops—plus plenty of walking for those who enjoy exploring on foot.

Add nearby Jamestown Settlement and Yorktown, along with modern attractions like Busch Gardens, and you have a destination that truly offers something for everyone.

Before you go: Planning your Colonial Williamsburg itinerary

Before your trip, go online at colonialwilliamsburg.org and visitwilliamsburg.com. These sites will help you make plans.

- Be sure to check out any special events happening during your visit—they abound most seasons.

- Save time by purchasing your tickets and making dining reservations online. Also, Viator offers a wide assortment of tours and experiences.

- Plan for a minimum of two days for a Williamsburg visit.

While roads circle the historic district, the streets inside the tourist area are closed to traffic. Begin at the Visitor Information Center, where parking is plentiful. You can use the hop-on/hop-off shuttle buses to traverse the perimeter of the historic city, offering multiple stops.

Teens and adults should not miss the introductory movie, Story of a Patriot. Yes, it was filmed in 1957 but restored beautifully. Where else can you catch a view of Jack Lord before his Hawaii Five-O days?

Guide to Colonial Williamsburg: the must-see historical buildings

While there is no right or wrong way to visit Williamsburg, the Capitol building offers an ideal starting point for your Colonial Williamsburg walking tour. What happened within its walls shall we say, brewed discussions leading to discontent, the Revolutionary War, and the eventual formation of the independent United States.

Capitol building

The original Capitol, completed in 1705, functioned as a two-story H-shaped structure, connecting two buildings by an arcade. Each wing served one of the two houses of the Virginia legislature, the Council and the House of Burgesses.

The building burned in January 1747, and a second built on the same site suffered the same fate.

Today’s replica Capitol, on the same foundations and per the same plans, became one of the first sites to open in February 1934. Guided tours start in the General Courtroom, the highest judicial court in the colony.

The bay features stunning woodwork and round windows. In the House of Burgesses, you can see the original 1735 Speaker’s chair. Council and Conference Rooms occupy the second floor.

Governor’s Palace

Before gaining independence, British royal rule in Virginia came locally– a royal governor. A grand brick structure, irreverently nicknamed “the Palace” by colonial subjects, was built in 1714.

The overall design sought to impress visitors with a display of authority and wealth, and it does indeed. The Governor’s Palace became the home to seven royal governors until the last one fled.

Following the Revolutionary War, the structure acted as the executive mansion for the first two elected governors in Virginia— Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson. In 1780, the capital of Virginia moved to Richmond.

The main building succumbed to fire in 1781 while in use as a hospital for the American wounded at the Siege of Yorktown.

A tour of the Palace, reconstructed in the early 1930s, takes you through the front door into an entrance hall. You’ll find it lined with an ornate display of swords and muskets. (Many European castles and mansions feature similar presentations.)

The first floor also includes a parlor, dining room, and an office. A grand supper room and ballroom were added to the rear. Their bright blue and vibrant green paint surprises many visitors. According to Kim Ivey, a CW curator, “Every single item installed was done so for a well-documented reason.”

The tour exits into the lavish formal gardens that invite leisurely strolls. The plots incorporate clipped hedges, rectangular parterres, and garden species used in the early eighteenth century.

The boxwood maze at the Governor’s Palace.

Stunningly beautiful tulips fill the gardens in the springtime. Other highlights include a tree-shrouded tunnel walkway and boxwood maze that kids (and I) adore. Don’t miss it!

Some 90-acres and 25 smaller gardens remain open to the public around town.

Bruton Parish Church and Graveyard

Burton Parish Church at night. Photo by Debi Lander.

The steepled Bruton Parish Church was designed by Royal Governor Spotswood and completed in 1715. In 1907, this original building became the first structure to undergo restoration.

Rev. Goodwin used this example to convince John D Rockefeller, Jr. to commit funds to bring back the historical city. The big dreams of these two men helped spark the restoration movement around the world.

The Bruton Parish Church and graveyard both invite explorations. Two of Martha Washington’s children rest there.

If possible, attend one of the evening candlelight harpsichord and organ concerts in the sanctuary. It’s hard to describe the lost-in-time feeling that period instruments, candlelight, old pews (maybe a seat George once occupied) create.

Raleigh Tavern

The Raleigh is open for tours, not like several others serving today’s guests with period dining, drinking, and music. Learn how the building functioned as an important social meeting place and a tavern for drinking, debate, and lodging.

One room contains a billiard table dating to 1738. Outback lies a large kitchen.

In the summer of 1956, I was a young girl visiting Colonial Williamsburg with my family for the first time. We finished a tour in the Raleigh Tavern when the clouds burst open. We scurried into the rear kitchen building, cramming in with many others.

A delightful aroma of gingerbread baking in the beehive oven surrounded us. The scent became irresistibly enticing, and everyone bought cookies handed over in brown paper sacks.

My cookie was so yummy the memory and smell still linger in my brain. Make sure to buy one or make your own using the recipe in this blog post: Williamsburg Gingerbread Cookies.

Duke of Gloucester Street

You will walk back and forth along the lengthy street packed with homes, taverns, craftsmen, and merchant shops. Look for colorful signs hanging outside that denote the type of craft.

Stop into the 1770 Courthouse and the Powder Magazine, where the town’s artillery was stored. If you haven’t read my story on the Gunpowder Incident in 1775, please find it here. Peruse the outdoor Market Square, perhaps buying a tri-corner hat or sunbonnet.

You may be lucky enough to see a musket or cannon firing or the fife and drum corps. Be sure to make a reservation and take a carriage ride.

Turn off the main route onto the Palace Green lined with catalpa trees. It remains one of my favorite places to sit, rest, and contemplate the people who lived here in the past.

If time permits and your legs aren’t too weary, join a guided tour inside the nearby Peyton Randolph House or the brick home of lawyer George Wythe.

A nighttime stroll becomes one of the loveliest ways to absorb the atmosphere along Duke of Gloucester. Lanterns light the way while candlelight glow seeps from house and tavern windows.

If you’re an early riser, meander Duke of Gloucester before it comes alive for the day. The setting evokes a marvelous sleepy feel, especially when foggy. Or consider joining the college students and fitness enthusiasts jogging the mile-long stretch.

The Wren Building at the College of William & Mary

Most first-time visitors don’t get around to touring the Wren Building on the campus of William & Mary. It ranks as the oldest college building in the United States, built between 1695 and 1699, even before Williamsburg’s founding. The college itself was chartered in February 1693 by King William III and Queen Mary II.

At least take a sightseeing drive around the beautiful 1,200-acre campus. The grounds incorporate ponds, bridges, and sunken formal gardens, especially enchanting in spring.

The college’s modern Muscarelle Museum of Art, with 4,000 works, might also be of interest.

Craft Houses/Demonstrations

The craftsmen working their trades fascinate all visitors, young and old. They use 18th-century tools and techniques to apprentice in — and eventually master —woodworking, gunsmithing, or basket weaving, to name a few.

These world-renowned experts make goods for sale or for use by other institutions around the world. They welcome questions.

Children are drawn to the blacksmith, shoemaker, milliner (hat maker), and brickyard. When possible, kids can even create a brick. Did you know the bricks and nails used for Williamsburg reconstructions were handmade there, just like the originals?

Most tourists don’t understand the research behind the authenticity of this destination, rarely found elsewhere. Colonial Williamsburg presents the accurate location and design of homes and buildings where our forefathers lived and worked.

Museums

Leave the Wiliamsburg museums for a second day, but explore the expanded joint venture: the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum. See colorful and whimsical collections of toys, portraits, weathervanes, and much more in the Folk Art Museum. I could spend hours in these.

Take time to appreciate the beautifully crafted furniture, musical instruments, home goods, textiles, and artworks in the DeWitt Wallace. Don’t miss the famous Charles Wilson Peale portrait of George Washington. The site includes a fantastic gift shop and convenient café.

Anticipating Williamsburg? Turn those plans into reality!

Lodging: Enjoy a charming stay in Williamsburg with Booking.com. Choose from historic inns to modern hotels that reflect the area’s rich colonial history. It costs a bit more to stay in the historic district, but being able to wslk to everything becomes a big plus.

Entertainment: Step back in time with Viator in Williamsburg! Explore reenactments and historical sites that bring American history to life in this iconic colonial town.

Dining in Colonial Wiliamsburg

Although the food served in the taverns traces back to similar fare cooked by colonists, the preparation takes place in modern kitchens. The servers, however, are dressed in period clothing.

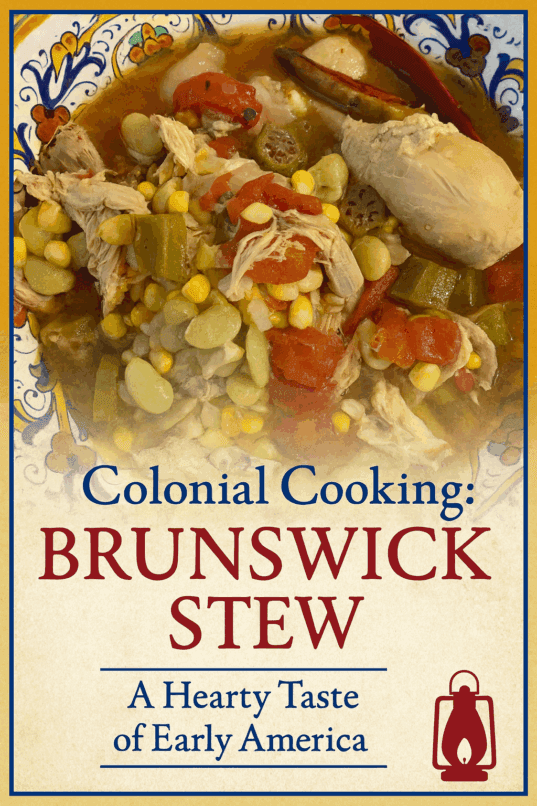

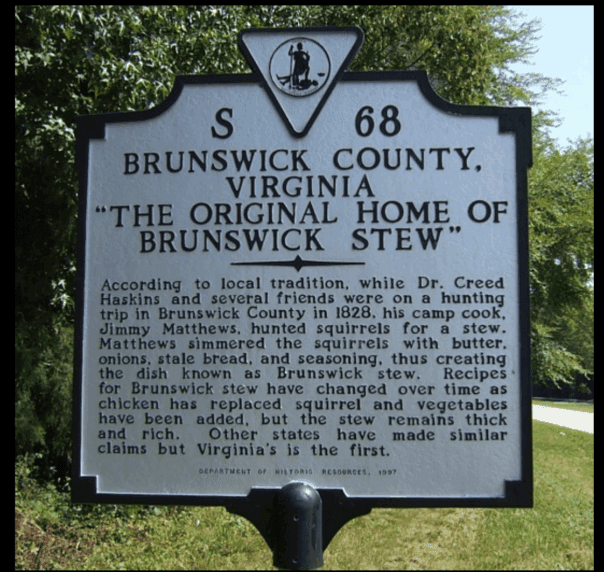

The dishes, flatware, and goblets are authentic reproductions of 18th-century items. Minstrels frequently provide musical entertainment. Look forward to tasting Peanut Soup, Sally Lunn bread, Brunswick Stew, or a syllabub.

- Christina Campbell’s Tavern: 101 South Waller St (behind the Capitol)

- Josiah Chowning’s Tavern: 109 East Duke of Gloucester St (temporarily closed)

- King’s Arms Tavern: 416 East Duke of Gloucester St

- Shields Tavern: 422 East Duke of Gloucester St

Where to stay in Colonial Williamsburg

To get the true feel for this historic city, I suggest you overnight in one of the Colonial Homes. I’ve done this three times, and each experience felt different, fun, and oh so memorable.

You choose between stand-alone colonial houses or a private room within a larger colonial home, known as a Tavern Room. Meticulously reproduced spaces resemble the period but with modern amenities. Rentals usually come with an admission pass.

My favorite lodging experience was spent in the Robert Carter Kitchen, tucked behind the house next to the Palace. I stayed there with my two daughters, and our little room was enchanting.

We could overlook grazing sheep, and the Palace illuminated at night. I reserved the last carriage ride of the day, and the driver dropped us off in front of “our” house! Talk about a memory.

Those looking for five-star and AAA Five-Diamond luxury should choose the iconic Williamsburg Inn. Many presidents and even the Queen of England have slept there.

No worries, if you can’t afford the rates, drop in and tour the property. Consider indulging with an extraordinary breakfast in the elegant Rockefeller Room or lunch in the Terrace Room overlooking the golf course.

The Williamsburg Lodge (now part of the Marriott Autograph Collection) offers a relaxing retreat, just steps away from all the action.

Williamsburg Woodlands becomes an excellent choice for a family. It conveniently rests next to the Visitor Center.

Nature surrounds the newest lodge, the Griffin Hotel, but it sits out of the historic district.

Other options not managed by Colonial Williamsburg include the sprawling Kingsmill Resort or the family-friendly Great Wolf Lodge.

More things to do in the Williamsburg area

Spa

Treat both your mind and body to a rejuvenating experience at The Spa (official website). Arrive early for your treatments and linger afterward to enjoy steam rooms, showers, and whirlpools, as well as the relaxation lounges.

Golf

Take your pick of 45-walkable holes over three courses at the Golden Horseshoe Golf Club designed by Robert Trent Jones and his son Rees Jones.

Shopping

I never miss browsing the goods in Prentis, Greenhow, and Tarpley’s, my favorite shops within the historic district. The Prentis Store showcases wares constructed using 18th-century techniques. Choose between handcrafted leather goods, iron hardware, tools, pottery, writing instruments, papers, ink, and seals.

The J. Greenhow General Store sells gifts, books, candy, historical items, toys, and trinkets. Their selection includes items imported from England for the colonists, like the delicate creamware dishes.

Tarpley’s, Thompson & Company, another fine shop, offers clothing, hats, and many of the above items.

Merchant’s Square

You will undoubtedly run into the area between the college and the historic car-free zone known as Merchants Square (official website). Hard to resist this retail village with over 40 modern-day shops and some fabulous restaurants, like the Blue Talon Bistro.

Be sure to check out the college bookstore or other stores selling souvenirs.

Christmas and the Grand Illumination

In the 18th century, illuminations — the firing of guns and lighting of fireworks — celebrated major events such as the birthday of a reigning sovereign, military victories, or a new colonial governor.

Williamsburg’s Grand Illumination began in 1935 with holiday candles in windows and fireworks. In the years that followed, the Grand Illumination became such a popular event that it expanded to three weekends.

Friday evenings introduced a new event, the Yule Log procession. It includes music from the Fifes and Drums, musket fire from Continental Army reenactors, and a visit from Father Christmas.

During a torch-lit march, the Yule Log progresses by wagon from the Capitol to Market Square. It then burns in a bonfire where guests gather to throw greenery sprigs into the fire and make a wish.

A grand display of fireworks is set off simultaneously rising above the Governor’s Palace and the Capitol on Saturday evenings.

Wreaths made from natural greenery with intricate designs of fruits, nuts, and pinecones decorate doorways and balconies. The homeowners and merchants go all out, hoping to win the annual local contest.

Having grown up in Northern Virginia, I am always excited to return to Williamsburg, one of my favorite places in the world. I look forward to dining in a colonial restaurant, shopping for handcrafted items, sitting in colorful gardens, and just soaking in the 18th-century ambiance.

Yes, Virginia is for lovers, and I do love Williamsburg.

How to get to Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg lies 150 miles south of Washington, D.C., midway between Richmond and Virginia Beach on Interstate 64. Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown make up the three corners of Virginia’s Historic Triangle. A 23-mile Colonial Parkway connects the sites.

Airports

Three airports serve Williamsburg within a 50-minute drive. Start your search for flights here.

- Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport (PHF) – a 20-minute drive.

- Norfolk International Airport (ORF) – a 50-minute drive.

- Richmond International Airport (RIC) – a 50-minute drive.

Train/Bus

City of Williamsburg Transportation Center, located in downtown Williamsburg, offers Amtrak, Greyhound Bus, rental car, and taxi services.