Bylandersea America 250 Series – Exploring the Road to Revolution

Boston—cradle of American liberty—was the stage where protest turned to rebellion and rebellion to revolution. Walking the city’s Freedom Trail today, visitors can trace the steps of patriots who risked their lives for independence. Two defining events unfolded here: the Boston Massacre of 1770 and the Boston Tea Party of 1773—fiery sparks that ignited the Revolutionary War.

Tension in the Streets: The Boston Massacre

By 1770, British troops occupied Boston to enforce unpopular taxes imposed by Parliament. Resentment simmered. On the cold evening of March 5, 1770, a crowd of angry colonists taunted soldiers guarding the Customs House on King Street (now State Street). Amid shouts and thrown snowballs, someone shouted “Fire!” The soldiers discharged their muskets, killing five men, including Crispus Attucks, a sailor of African and Native descent who became the first martyr of the Revolution.

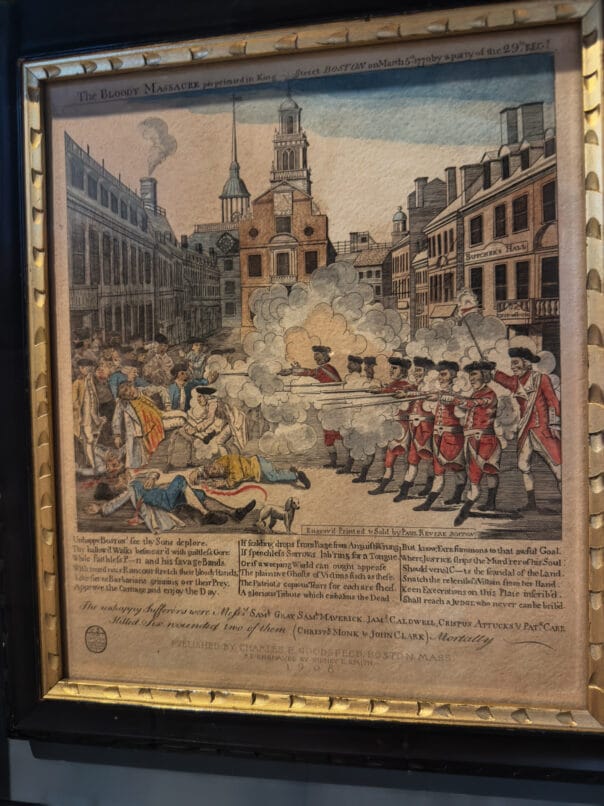

Patriot leaders like Paul Revere and Samuel Adams seized on the tragedy, publishing dramatic engravings that spread outrage across the colonies. Although lawyer John Adams defended the soldiers to ensure a fair trial, the “Boston Massacre” became a rallying cry against tyranny.

🕊 Freedom Trail Stop:

- Old State House – A cobblestone circle outside marks where the massacre occurred. Inside, the museum tells the story through eyewitness accounts, artifacts, and Revere’s engraving.

A Harbor Turned Teapot: The Boston Tea Party

Three years later, new taxes again stirred protest. The Tea Act of 1773 granted the East India Company a monopoly on tea sales, undercutting local merchants. To the colonists, it wasn’t about the price of tea—it was about taxation without representation.

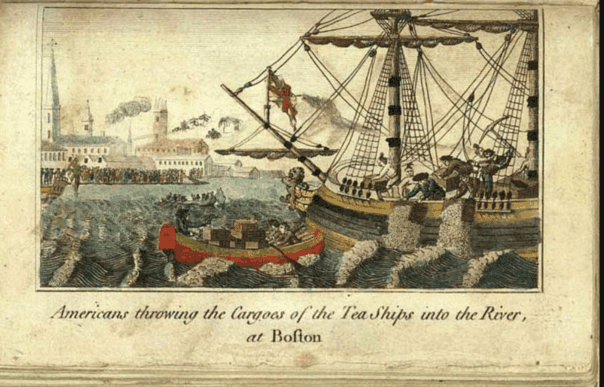

On the night of December 16, 1773, members of the Sons of Liberty, some disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded ships at Griffin’s Wharf. In just three hours, they dumped 342 chests of British tea—worth more than $1 million today—into the harbor.

The daring act provoked Parliament’s fury. The Coercive Acts, known in America as the Intolerable Acts, closed Boston’s port and tightened royal control. But the punishment backfired: the colonies united in resistance, paving the way for revolution.

☕ Freedom Trail Stops:

- Old South Meeting House – Where thousands gathered to debate the tea crisis before marching to the harbor.

- Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum – A floating interactive exhibit with replica ships, costumed interpreters, and the chance to toss a “tea chest” overboard yourself.

Walking the Freedom Trail

Stretching 2.5 miles through downtown Boston, the Freedom Trail connects 16 historic sites that tell the story of America’s struggle for liberty—from Boston Common to Bunker Hill Monument. Other essential stops include:

- Faneuil Hall, where fiery speeches inspired resistance.

- Old North Church, signaling “One if by land, two if by sea.”

- Paul Revere House, the patriot’s home in the North End.

Download a map from TheFreedomTrail.org or join a guided walk led by costumed interpreters for immersive storytelling.

Bylandersea’s Reflections

While Boston is a busy modern city, standing before the Old State House or the quiet waters of Boston Harbor, it’s easy to imagine the fear, anger, and hope that once filled these streets. The Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Party weren’t isolated moments—they were the awakening of a people determined to define liberty for themselves.

Do You Know? George Robert Twelves Hewes

I learned about this person while touring the Old State House in Boston. He’s one of those memorable hidden gems. (Sorry about the glare on the photo.)

George Robert Twelves Hewes was a Boston shoemaker who found himself swept up in the events that sparked the American Revolution. He witnessed the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, and later took part in the Boston Tea Party, helping to dump chests of tea into the harbor and even confronting a British officer during the chaos.

In 1775, Boston was put under martial law and, like many other patriots, Hewes fled the city. His first period of military service began in the fall of 1776 when he boarded the privateering ship “Diamond”. The voyage was successful, resulting in the capture of three enemy vessels. He served in many other battles and sea voyages until 1781 when his military career ended. After the war of 1812 Hewes and his family moved to Richfield Springs in Ostego County, New York. For the rest of his life, he was well respected in the community for his contribution to the cause of the American Revolution and was always a desired participant in memorial ceremonies.

For decades afterward, Hewes and the other Tea Party participants kept their identities secret. Fear of British retaliation—and later, a desire to preserve the unity of the new nation—kept many silent. Only in the early 1800s, when the Revolutionary generation was aging and public curiosity grew, did Hewes finally share his story.

The phrase “Boston Tea Party” was not used at the time of the event in 1773. The participants called it things like “the destruction of the tea” or “the affair of the tea.” They deliberately avoided drawing attention to themselves, since the act was illegal and potentially treasonous.

The name “Boston Tea Party” did not come into use until many decades later — around the 1820s to 1830s.

- The earliest known printed use of the phrase appears in 1825, in newspaper accounts reflecting on the Revolution’s 50th anniversary.

- It became common after 1834, when local histories and memoirs (including those of George Robert Twelves Hewes) began to romanticize the event.

- By the time of the centennial celebrations in 1873, “Boston Tea Party” was the established and widely recognized term.

So, for more than fifty years, Americans didn’t speak of a “Tea Party” at all — they spoke of “the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor.” The catchy name came later, part of the growing mythology of the Revolution.

By the time of his death in 1840 at age 98, he had become one of the last living witnesses to both the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party. His humble life and late fame reminded Americans that the Revolution’s heroes were not only generals and statesmen, but also ordinary citizens with extraordinary courage.

***

Next in the Bylandersea America 250 series, the story shifts south to Virginia, where Patrick Henry’s fiery words at Scotchtown echoed Boston’s defiance.

On a crisp, rainy September afternoon I pulled up to the bucolic

On a crisp, rainy September afternoon I pulled up to the bucolic

The following morning I awoke before dawn, hastily dressing for my 6:30 AM ride to the airport. Everyone else was asleep except for a friendly night watchman, who offered me a cup of coffee and a brief history of the place.

The following morning I awoke before dawn, hastily dressing for my 6:30 AM ride to the airport. Everyone else was asleep except for a friendly night watchman, who offered me a cup of coffee and a brief history of the place.