Baby Boomers and earlier generations in the United States learned that Plymouth, Massachusetts, was America’s birthplace and home of the first Thanksgiving. Many schoolchildren crafted Pilgrim hats and feathered headdresses, re-creating a simplified story. Today we know other settlements preceded Plymouth, and historians debate the authenticity of Plymouth Rock, yet the town still stands as a powerful symbol drawing thousands of visitors each year.

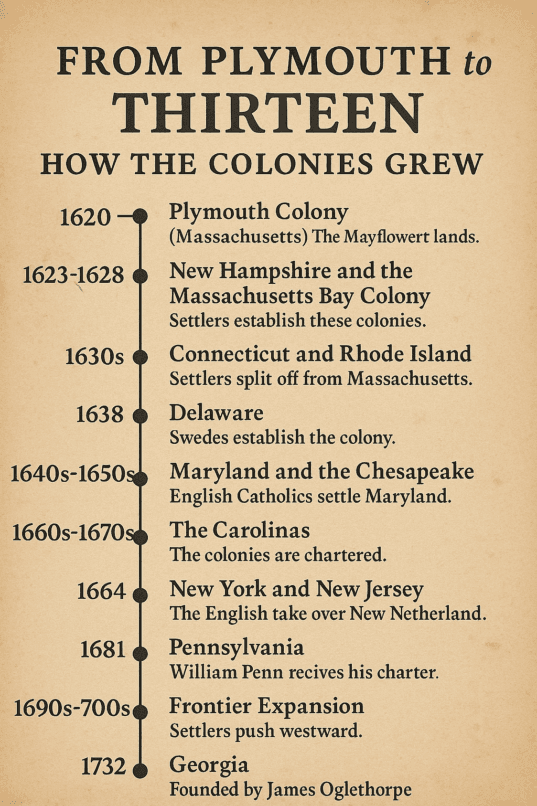

This post is part of my Bylandersea American Revolution 250 series. In previous articles I explored Roanoke Island, site of the Lost Colony and Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement. Now let’s take a closer look at the real Plymouth story—and what you can see today.

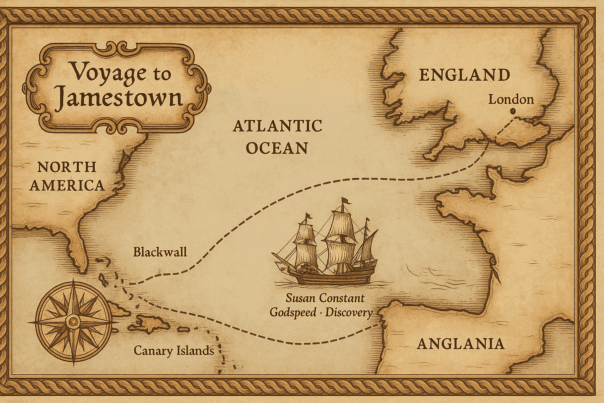

The Voyage of the Mayflower

In September 1620, a group of English Separatists—later known as the Pilgrims—joined with other settlers to sail to the “New World.” The Separatists were English Protestants who believed the Church of England had not gone far enough in breaking from Roman Catholic practices. Rather than reform from within, they separated entirely, forming their own congregations in defiance of English law. Many fled to the Netherlands to worship freely; some of them later became part of the group that sailed on the Mayflower to establish a new community in North America.

The Mayflower was a merchant ship measuring just 106 feet long and 25 feet wide. Originally the group planned to sail with a companion vessel, the Speedwell, but that ship leaked repeatedly and had to turn back. This left the Mayflower overcrowded with about 102 passengers plus a crew of roughly 30. Departing from Plymouth, England, on September 16, 1620, they faced rough autumn storms, cramped and unsanitary conditions, and disease. With limited fresh food and little privacy, passengers endured more than 66 days at sea—nearly twice as long as a summer crossing.

Do You Know?

During a violent storm on the Atlantic, a young steward named John Howland was swept overboard from the Mayflower. He caught a rope and was hauled back to safety—a miracle that changed history. Howland survived, married fellow passenger Elizabeth Tilley, and together they raised ten children. Today, their descendants include three U.S. Presidents: Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush.

Landfall and Settlement

The Mayflower was bound for the Virginia Company’s territory near the Hudson River, but storms and navigational challenges pushed it north. In 1620 the Virginia Company’s charter extended far beyond today’s Virginia, up past the Hudson into what we now call New York. The passengers had permission to settle near the mouth of the Hudson, but by the time land appeared they were at the tip of Cape Cod, and outside their patent. That uncertainty led to the signing of the Mayflower Compact before going ashore, pledging self-government and loyalty to the king—an early step toward democratic governance in America.

After weeks of exploring the coast, the group crossed the bay to a site the Wampanoag called Patuxet. Here they found an abandoned Native village and fresh water, making it an ideal location for settlement. They named it Plymouth, after their port city in England. In December 1620 the Pilgrims began building simple wooden homes on the hillside above the harbor, enduring a harsh winter that claimed nearly half their number.

Through a tenuous alliance with the Wampanoag, and with critical help from individuals like Tisquantum (Squanto), the settlers learned how to plant corn, fish local waters, and adapt to the new environment. Their survival led to the growth of Plymouth Colony—the oldest continuously inhabited English settlement in New England—and the enduring story of their arrival became a cornerstone of American identity.

Why It Matters

Religious Freedom & Self-Government

The Mayflower Compact is often cited as a foundation for later American political principles.

Cultural Encounter

The Pilgrims’ survival depended on interactions with the Wampanoag people, notably Squanto, who taught them local agriculture and acted as mediator.

Heritage

Plymouth has become a symbolic birthplace of New England and an enduring touchstone of the American story.

Where Was the First Thanksgiving?

Plymouth’s Claim (1621)

After their first successful harvest, about 50 surviving Pilgrims and 90 Wampanoag guests shared a three-day feast. Governor William Bradford described the event in Of Plimoth Plantation. This gathering, though not called “Thanksgiving” at the time, became the traditional model for the holiday we celebrate today.

Other Claimants

Several other sites argue for an earlier “first Thanksgiving”:

– St. Augustine, Florida (1565): Spanish explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and his crew held a Mass of Thanksgiving and shared a meal with the Timucua people.

– Berkeley Hundred, Virginia (1619): English settlers arriving on the James River held a day of Thanksgiving as part of their charter—explicitly called a “thanksgiving” in records.

– El Paso, Texas (1598): Juan de Oñate led a Spanish expedition and celebrated a Thanksgiving Mass and feast after crossing the desert to the Rio Grande.

Despite these precedents, Plymouth’s 1621 harvest feast became the holiday’s symbolic origin because it fit the emerging American narrative: a story of English colonists, Native American allies, and self-governance that resonated with 19th-century New England writers and educators. By the time Abraham Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863, the Plymouth version had become the most widely accepted.

Do You Know? Squanto – The Pilgrims’ Lifeline

Born around 1585 near today’s Plymouth, Squanto was a member of the Patuxet band of the Wampanoag people. Kidnapped by English traders, taken across the Atlantic, and sold into slavery in Spain, he escaped to England, learned the language, and returned to New England around 1619 to find his village wiped out by disease. Despite this loss, in 1621 he taught the Pilgrims vital skills—how to plant corn with fish as fertilizer, where to find eels and shellfish—and acted as translator and mediator with the Wampanoag sachem Massasoit. Governor Bradford later called him “a special instrument sent of God for their good.” His story intertwines tragedy, resilience, and cross-cultural exchange—reminding us that Plymouth’s survival was not solely a Pilgrim achievement but also a testament to Indigenous expertise and generosity.

Do You Know? William Bradford – Plymouth’s Governor and Chronicler

William Bradford (1590–1657) was a key figure in the survival and shaping of Plymouth Colony. Drawn to the Separatist movement as a teenager, he fled to the Netherlands and later sailed on the Mayflower with his wife, Dorothy, helping draft and sign the Mayflower Compact. After Governor John Carver died in the spring of 1621, Bradford was elected governor—a role he held for more than 30 years. His manuscript, Of Plimoth Plantation, offers the most detailed first-hand account of the Pilgrims’ journey, struggles, and spiritual motivations. Without his writings, much of what we know about the Mayflower voyage and the early years in Plymouth would be lost.

Visiting Plymouth Today

Today, Plymouth offers travelers a layered experience: you can trace early colonial footsteps, meet costumed interpreters, and see how the town’s narrative continues to evolve more than 400 years later. (I visited Plimoth Plantation many years ago, before digital cameras! )

Historic Highlights

Pilgrim Memorial State Park & Plymouth Rock: On the waterfront, the granite canopy sheltering Plymouth Rock marks the symbolic landing site. While historians debate the rock’s authenticity, standing here is a rite of passage for visitors.

Mayflower II: A full-scale reproduction of the original ship built in England and sailed to Plymouth in 1957. Step aboard to imagine the cramped conditions endured by 102 passengers during their 66-day voyage. The vessel recently underwent a major restoration and features new interpretive exhibits.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums (formerly Plimoth Plantation): This living-history museum immerses guests in two worlds: a 17th-century English village where interpreters portray actual colonists, and a Wampanoag homesite where Indigenous staff share their people’s perspective, crafts, and traditions.

–Burial Hill & Historic Downtown: The town’s original graveyard crowns a hill with sweeping harbor views. Weathered stones date to the 1600s, including that of Governor William Bradford. Nearby, downtown Plymouth brims with historic houses, churches, and seafood restaurants.

Planning Tips

– When to Go: Spring through fall brings mild weather and a full calendar of living-history events. November sees special programs around Thanksgiving.

– Tickets: Plymouth Rock is free to view, but Mayflower II and Plimoth Patuxet Museums require paid admission (combo tickets available).

– Duration: A full day lets you see the main sites; a weekend allows time for nearby Cape Cod or Boston side trips.

– Accessibility: All major attractions have visitor centers, restrooms, and gift shops. Parking can be limited in high season—arrive early.