I’m launching my BylanderseaAmerica250 blog series where America’s colonial story begins—on Roanoke Island. Here, the first English settlers vanished without a trace, leaving behind only haunting clues and unanswered questions. Long before independence stirred in the 13 Colonies, these early pioneers crossed the Atlantic under the English Crown, their fate forever shrouded in mystery.

The First Attempt at a New World Dream

Roanoke Island holds one of America’s greatest unsolved mysteries—the story of the Lost Colony. Let’s step back to 1584, before Plymouth Rock and even before Jamestown, to Roanoke — England’s earliest attempt to establish a colony in the New World. And though the settlement disappeared, the story it left behind continues to spark imaginations over 400 years later.

In 1584, Queen Elizabeth I granted Sir Walter Raleigh a charter to establish colonies in the New World. That year he sent an expedition led by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to explore what is now North Carolina’s Outer Banks. They made contact with the Algonquian peoples, and reported favorably on the land. Two of the indigenous tribe members. Manteo and Wanchese, traveled back to England with them.

In 1585, Raleigh sent a larger group of approximately 600 men under Sir Richard Grenville, although fewer actually stayed. The military settlement faced supply shortages, poor relations with Native groups, and harsh conditions.

In 1586, after almost a year, the soldiers abandoned Roanoke and returned to England with Sir Francis Drake, who had stopped by after raiding the Caribbean.

Then, in 1587, a group of 117 men, women, and children led by Governor John White landed on Roanoke Island, today’s Outer Banks, aiming to create a permanent settlement. White had been chosen Governor of the “Cittie of Raleigh,” the official name given to the colony under Raleigh’s patent from the Queen. The colonists included White’s daughter, who soon gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the Americas.

White returned to England for supplies but was delayed by war with Spain. When he finally made it back three years later, he found the settlement abandoned, the houses dismantled, and a single clue carved into a post: “Croatoan.” No sign of struggle. No graves. No survivors. Theories abound: Did the colonists assimilate with Indigenous peoples? Perish in a storm? Flee elsewhere? No definitive answer has ever been found. That milestone should have been the beginning. instead, it became the prologue to a riddle history has yet to solve.

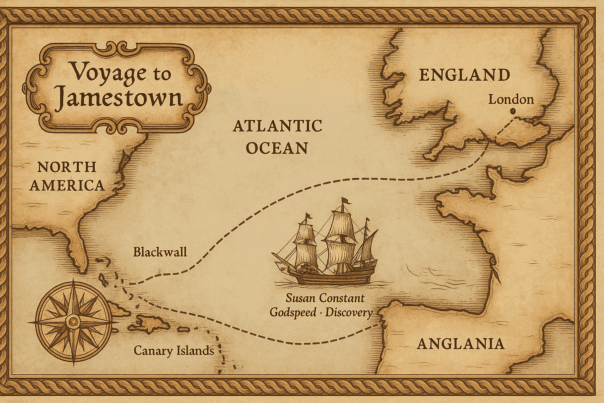

Voyage to Roanoke: The 1587 Crossing

For the settlers, the ordeal of Roanoke began long before they vanished—it began at sea. In May of 1587, they boarded the Lion, leaving England’s familiar shores for an uncertain world. Transatlantic voyages in the 16th century followed the trade winds: first south toward the Canary Islands, then westward across the open ocean, often stopping in the Caribbean before turning north toward the Outer Banks.

The journey took about two to three months under the best conditions. Life aboard was cramped, damp, and constantly in motion. Food consisted mainly of salted meat, hardtack biscuits, dried peas, and beer or weak ale for hydration. Fresh water quickly turned stale.

The passengers endured storms, unpredictable winds, and the ever-present threat of shipwreck or piracy. Seasickness was common, and illness could spread rapidly in the close quarters. Nights were lit only by lanterns swaying in the dark, the air heavy with the scent of tar, wet rope, and unwashed bodies. (I cannot image enduring this voyage.)

By the time the settlers finally glimpsed the sandy coast and dense forests of Roanoke Island in late July, their arrival was both a relief and the start of a new set of challenges—ones that would prove even more dangerous than the ocean crossing.

The Vanishing

Only weeks after their arrival, tensions rose. Supplies were scarce, and relations with local Indigenous tribes—strained from an earlier English expedition—were uncertain. Governor White sailed back to England to plead for aid, intending to return quickly.

But fate intervened. England became embroiled in war with Spain, and White’s return voyage was delayed again and again. It was not until three long years later, in 1590, that he finally made it back to Roanoke.

What he found was chilling. The settlement stood deserted. Houses had been dismantled, not destroyed, as if taken down deliberately. There were no signs of battle—no scattered belongings, no graves. Only one clue remained: the word CROATOAN carved into a post. Despite archaeological digs and modern DNA research, no solid evidence has emerged. Roanoke remains a ghost story with no ending, its truth buried beneath sand, water, and time.

Let’s Walk Where They Walked

When I visited Roanoke Island, the mystery seemed to hover in the air. Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, managed by the National Park Service, preserves the approximate location of the colony. The reconstructed earthen fortifications curve gently under the pines, their grassy embankments whisper of watchful days and tense nights. Interpretive signs sketch the outlines of history, but your mind must fill in the rest.

During the summer, the long-running outdoor drama The Lost Colony plays at the Waterside Theatre, where actors in Elizabethan costume perform under the stars, their voices carrying across Roanoke Sound. The performance is part history, part haunting, drawing you into the settlers’ hopes and fears as if you are watching events unfold in real time.

What to See and Do When Visiting Roanoke Island

1. Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

Walk the trails, explore the reconstructed earthworks, and view exhibits on the Lost Colony’s history. Don’t miss the short film at the visitor center for essential background before stepping onto the historic grounds.

2. The Lost Colony Outdoor Drama

This Tony Award–winning play is the longest-running outdoor symphonic drama in the U.S., staged each summer since 1937. Arrive early to enjoy the setting sun over Roanoke Sound.

3. Elizabethan Gardens

A peaceful tribute to the colonists, featuring seasonal blooms, formal hedges, a sunken garden, and statuary, all inspired by 16th-century English design. A bronze sculpture of Virginia Dare stands as a poignant reminder of the colony’s most famous child.

4. Roanoke Island Festival Park

Perfect for families and history buffs alike. The park allows for immersive experiences: climb aboard a replica ship, visit a recreated Algonquian village, don a costume like I did, and explore the museum’s hands-on exhibits.

5. Downtown Manteo

This charming waterfront town, named for the Algonquian, is just minutes from Fort Raleigh. Browse boutique shops, enjoy fresh seafood, and stroll along the boardwalk with views of Shallowbag Bay.

Getting to Roanoke Island & Exploring the Outer Banks

Roanoke Island sits in North Carolina’s Outer Banks, a narrow ribbon of barrier islands edging the Atlantic. Most visitors arrive by car.

By Car

• From the north: follow US Highway 158 through Kitty Hawk, crossing the Wright Memorial Bridge, then south on US 64/264 to Roanoke Island.

• From the west: take US Highway 64 across the Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge.

• From the south: cross the Marc Basnight Bridge at Oregon Inlet.

By Air

• Closest airport: Norfolk International (ORF), about a two-hour drive.

• Other options: Raleigh–Durham (RDU) or Pitt–Greenville (PGV), 3–4 hours away.

Getting Around

Public transportation is limited. A rental car is the best way to explore. Allow extra time in summer—the two-lane highways can be slow, but the water views and sand dunes make for a scenic ride.

Don’t Miss Sites in the Outer Banks

• Wright Brothers National Memorial (Kill Devil Hills): Stand on the very ground where Orville and Wilbur achieved the first powered flight in 1903. The reconstructed camp buildings and soaring granite monument are inspiring.

• Jockey’s Ridge State Park (Nags Head): Climb the tallest natural sand dune system on the East Coast for sweeping views, sunsets, and hang gliding.

• Cape Hatteras National Seashore: Drive south for wild beaches, iconic lighthouses (including Cape Hatteras Light, the tallest in the U.S.), and the chance to spot wild ponies.

• Corolla & Carova: Head north to see the famous wild horses roaming freely along the beaches. Tours are available in 4×4 vehicles.

• Bodie Island Lighthouse: A black-and-white striped beauty, open for seasonal climbs.

Visitor Tips

- Best Time to Visit: Spring and fall offer mild weather, while summer brings outdoor performances and vibrant gardens.

- Tickets: Purchase tickets to The Lost Colony in advance, especially during peak summer weeks.

- Allow Time: Plan at least a half-day to explore Fort Raleigh, the gardens, and the town of Manteo.

- Free Outer Banks Visitor Guide: https://www.outerbanks.org/plan-your-trip/travel-guide

Why Roanoke Still Matters

Roanoke Island’s mystery endures because it speaks to the fragility of human ambition. The Lost Colony was meant to be a foothold in a new world, but instead became a reminder of how swiftly dreams can vanish. Yet, it also left behind something remarkable: a story that refuses to die, capturing the imagination of historians, playwrights, novelists, and curious travelers.

Standing among the pines at Fort Raleigh, you can imagine the voices of the colonists in the wind, calling across time – or did the Outlander tv series make me think that way? Perhaps that is Roanoke’s greatest legacy—not the disappearance itself, but the fact that we are still listening and wondering.

Did You Know?

Sir Walter Raleigh named the territory “Virginia,” and other trivia.

Few names are as entwined with the mystery of America’s first English colony as Sir Walter Raleigh. Born in Devon, England, in 1552, Raleigh grew to prominence as a courtier, soldier, poet, and explorer during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. His charm and daring won the Queen’s favor, and in 1584 she granted him a charter to establish colonies in the New World. England hoped these settlements would expand its power, rival Spain, and tap into the riches of newfound lands.

Raleigh never personally set foot on Roanoke Island, but his vision and resources set the venture in motion. The first expedition returned with glowing reports of fertile land and friendly native peoples. Enthused, Raleigh named the territory “Virginia” in honor of the Virgin Queen.

A more ambitious attempt followed in 1585, when a group of soldiers and craftsmen established a military outpost on Roanoke. Harsh conditions, strained relations with local tribes, and poor planning doomed the colony. Undeterred, Raleigh organized another effort in 1587, this time sending families under the leadership of John White. They hoped to build a permanent settlement. White’s granddaughter, Virginia Dare, became the first English child born in America.

But Raleigh’s dream unraveled into one of history’s greatest puzzles. When White returned from a supply trip to England, delayed by war with Spain, he found the settlement deserted. The only clue was the word “CROATOAN” carved into a post. The fate of the “Lost Colony” remains unsolved to this day.

Though Roanoke failed, Raleigh’s bold gamble laid the groundwork for future English settlements. His name is forever linked with the spirit of adventure, ambition, and mystery of Roanoke Island.

Trivia Tidbits

In 1972, the city of Raleigh was named in honor of Sir Walter Raleigh and is the capital of North Carolina.

The Raleigh Tavern took its name from Sir Walter Raleigh, the prominent Elizabethan courtier and explorer who sponsored England’s first attempt to colonize North America on Roanoke Island.

The Raleigh Tavern, built sometime before 1735, became one of colonial Virginia’s most prominent social and political gathering spots. The site hosted dances, auctions, receptions for royal governors, and most critically, became a refuge for Virginia legislators when the House of Burgesses was dissolved by Governor Botetourt. In the famed Apollo Room, these former Burgesses met, adopted the Non-Importation Agreement, and rallied revolutionary sentiment.