By Debi Lander for BylanderseaAmerica250

By the summer of 1777, the American Revolution remained a fragile experiment. George Washington had saved the Continental Army at Trenton and Princeton, (be sure to read about the famous crossing of the Delaware if you missed it: here), but survival alone would not secure independence. The army was still poorly supplied, unevenly trained, and constantly short of men. Enlistments expired. Desertions continued. Victory had proven possible, but the outcome of the war was far from certain.

British leaders believed time was on their side. If the colonies could be isolated and divided, the rebellion would collapse under its own weight. Military defeat was only one option. Political exhaustion and geographic separation might accomplish the same goal.

To that end, British commanders devised a sweeping plan to regain control of the Hudson River corridor, the natural spine of the colonies. Control the Hudson, and New England would be cut off from the middle and southern colonies. The heart of the rebellion would be isolated.

The task fell to John Burgoyne, a confident and ambitious British general. Burgoyne would march south from Canada with a large army, supported by artillery, German mercenaries, and Native allies. He expected to meet up with British forces advancing north from New York City. Together, they would crush American resistance in the region.

On paper, the plan appeared decisive.

In reality, it depended on flawless coordination, reliable supply lines, and terrain that proved anything but cooperative.

The Road South

Burgoyne’s army moved slowly through the forests and marshes of northern New York. Roads were little more than rough tracks. Heavy cannons sank into mud. Wagons broke down. Supplies lagged behind. Every mile south came at a cost.

American forces understood the land in ways the British did not. They cut down trees to block roads, destroyed bridges, and launched constant small attacks that wore down British troops. What the British viewed as empty wilderness was home territory for colonial farmers and militia.

At Fort Ticonderoga, the British achieved an early and symbolic success. The fortress that had once supplied Henry Knox with cannon for the Siege of Boston fell quickly. For a moment, it appeared Burgoyne’s campaign was on track.

But the victory drained time and resources. American forces withdrew rather than fight a costly battle. Burgoyne pressed on, growing more isolated with each step south.

By late summer, his army was deep in hostile territory with stretched supply lines and no sign of support from New York City.

Saratoga: Two Battles, One Surrender

In September 1777, British and American forces collided near Saratoga, New York, along the Hudson River. The first major engagement took place at Freeman’s Farm. It was a brutal and confusing battle. British troops advanced but failed to break American lines. Casualties mounted on both sides. Burgoyne held the field but gained no decisive advantage.

Weeks later, the armies clashed again at Bemis Heights. This time, the Americans were ready.Under the leadership of General Horatio Gates and field commanders who understood the terrain, American troops entrenched themselves along strong defensive positions. Militia units and Continental soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder against seasoned British regulars.

One of the most controversial figures of the Revolution, Benedict Arnold, played a decisive role. Though officially sidelined by command disputes, Arnold charged into battle and led fierce assaults that broke British lines. His courage and recklessness helped turn the tide of the fight.

The British advance collapsed. Burgoyne’s army was surrounded, short on food, and out of options.

On October 17, 1777, Burgoyne surrendered his entire force. It was the first time a full British field army had been defeated and captured in the war.

Why Saratoga Changed Everything

The victory at Saratoga transformed the American Revolution. Until that moment, foreign powers had watched cautiously. Sympathy for the American cause existed, but support remained unofficial.

News of Burgoyne’s surrender crossed the Atlantic with stunning speed. In Paris, French leaders recognized what Saratoga represented. The Americans were not simply resisting. They were capable of defeating Britain in open battle.

Within months, France formally allied with the United States. French money, supplies, naval power, and troops would soon enter the war.

The conflict expanded beyond North America. It became a global struggle. What began in village greens, frozen river crossings, and forest skirmishes had grown into an international war for independence.

Belief in the America cause proven itself worthy.

Bylandersea America 250 Travel Guide

Key Revolutionary Sites to Visit

1. Saratoga National Historical Park

Where the course of the war shifted

This is the heart of the story. Saratoga is not one battlefield but a landscape of rolling fields and wooded ridges that look peaceful today, but in 1777 they witnessed the moment Britain lost its best chance to crush the rebellion.

Estimated Visit Time

2 to 3 hours minimum

Add time if walking multiple battlefield trails

What to See

- Visitor Center for orientation and exhibits

- Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights battlefield stops

- Saratoga Monument for panoramic views

Official Site

https://www.nps.gov/sara

2. Schuyler House

Headquarters of American planning and diplomacy

This refined Georgian home served as a center of strategy during the Saratoga campaign. It was also the setting for Burgoyne’s surrender discussions. The contrast between elegant rooms and wartime decisions makes this stop especially powerful.

Estimated Visit Time

60 to 90 minutes with guided tour

Why Stop Here

- Site of surrender negotiations

- Insight into how civilian homes became wartime command centers

- Excellent interpretation of leadership and diplomacy

Official Site

https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/19/details.aspx

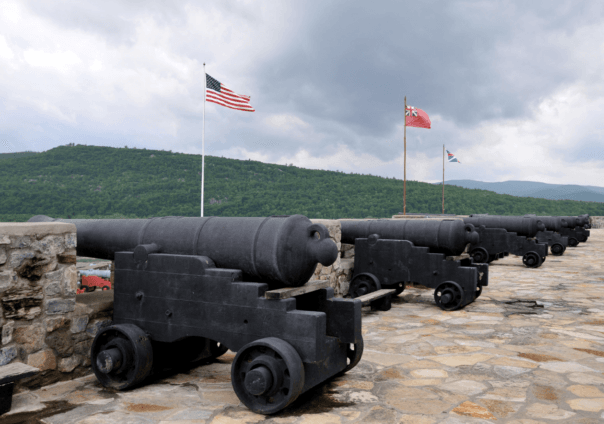

3. Fort Ticonderoga

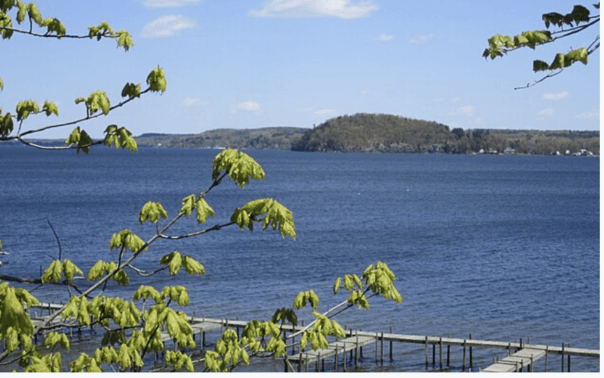

From British victory to American resilience. I have not visited this site for many years, but encourage it.

Few places better illustrate the uncertainty of the Revolution’s middle years. Captured early by Americans, retaken by the British, and ultimately part of Burgoyne’s downfall, Fort Ticonderoga shows how victories can carry unintended consequences.

Estimated Visit Time

3 to 4 hours

A half day if attending demonstrations or reenactments

Highlights

- Restored fort and barracks

- Extensive museum collections

- Lake Champlain and mountain views

Official Site

https://www.fortticonderoga.org

4. Hudson River Valley

The strategic corridor Britain failed to control

The Hudson River Valley was the lifeline of the colonies and the centerpiece of British strategy. Control it, and New England would be isolated. Lose it, and the rebellion would remain connected.

4

The Hudson River Valley explains why Saratoga mattered. This river connected the colonies economically and militarily. British plans depended on controlling it. American resistance ensured that never happened.

- Scenic drives along the river

- Historic towns and overlooks

- Easy to combine with Saratoga and Albany

Official Resource

https://www.hudsonrivervalley.com

Driving Distances and Order

Recommended Route

- Fort Ticonderoga to Saratoga National Historical Park

Approx. 70 miles

About 1 hour 45 minutes - Saratoga National Historical Park to Schuyler House

5 miles

About 10 minutes - Saratoga to Albany or Hudson River Valley drive

30 to 60 miles depending on route

45 to 90 minutes

This route follows the historical flow of the campaign from north to south.

Together, these sites tell the story of strategy, sacrifice, and the moment when the world began to believe America might win.