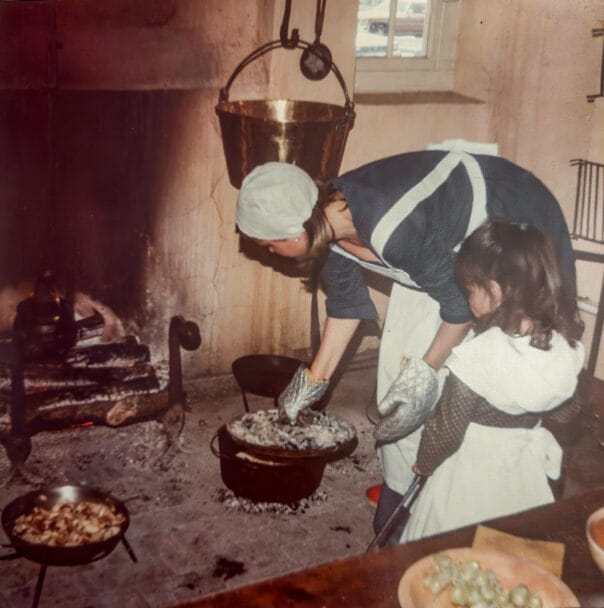

As part of my BylanderseaAmerica250 blog series, I plan to share historic recipes from time to time. Many years ago, I volunteered as an open-hearth cooking docent for the Camden County, NJ Historical Society. That experience sparked my love of colonial-period recipes—some of which I still prepare today.

Food in colonial America wasn’t simply about taste; it was about survival. Early settlers arrived to an unfamiliar climate and landscape, often with limited supplies. They had to learn quickly what would grow, what game could be hunted, and how to preserve food through long winters.

Lessons from the Land and Its People

Native Americans played a vital role in shaping colonial diets. They introduced the newcomers to a variety of foods that became staples in the colonies. Chief among these was corn, or maize, a crop unknown in Europe but already the backbone of many Indigenous diets. Native peoples taught colonists how to plant corn in mounds with beans and squash—the “Three Sisters” method—which replenished soil nutrients and produced a balanced harvest. They also showed the colonists how to grind dried corn into meal for breads, mush, and porridge. Recipes evolved into staples such as johnnycakes and hoe cakes.

Beyond corn, Indigenous communities shared knowledge about beans, pumpkins, wild rice, cranberries, and local herbs. They passed on methods of smoking and drying meat and fish, enabling colonists to preserve protein through the lean months. Without these lessons, many early settlers might not have survived.

Settlers adapted English recipes to the ingredients at hand. Stews, chowders, and corn-based breads became daily fare. A typical colonial meal might feature a pot of vegetables and salt pork, corn mush with milk, or roasted game accompanied by whatever seasonal produce was available.

Indian Pudding

In this post, I’m sharing a classic: Indian Pudding. Its name reflects the influence of Indigenous people who introduced corn to the early settlers and taught them to eat it in countless forms—roasted, boiled in soups and stews, mashed, dried, ground into cornmeal, or baked. Indian Pudding uses cornmeal and molasses, making it both hearty and lightly sweet. The custard like concoction can be served as a side dish or dessert, and it makes a wonderful addition to a Thanksgiving table as a conversation starter about our shared food heritage.

Today, preparation is easy: you simply bake it in the oven. But in colonial times, the pudding might be cooked in a Dutch oven or a heavy pot nestled into hot coals by the hearth.

Recipe for Indian Pudding

- 3 cups milk

- ½ cup molasses

- 1/3 cup cornmeal

- ½ teaspoon ground ginger

- ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon

- ¼ teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon butter

In a saucepan, mix the milk and molasses; stir in the cornmeal and spices. Cook and stir until thickened, about 10 minutes. Pour into a 1-quart casserole. Bake uncovered at 300°F for about one hour (or longer if the middle seems uncooked). Serves 6–8, hot or cold.

Colonial Cooking: Why It Matters Today

Colonial cooking tells a story not only of hardship but of cultural exchange and adaptation. The blending of Indigenous and European foodways laid the foundation for American cuisine as we know it. When you bite into cornbread, enjoy a Thanksgiving pumpkin pie, or spoon up a chowder, you’re tasting history that began in those earliest kitchens.