Life in the Thirteen Colonies

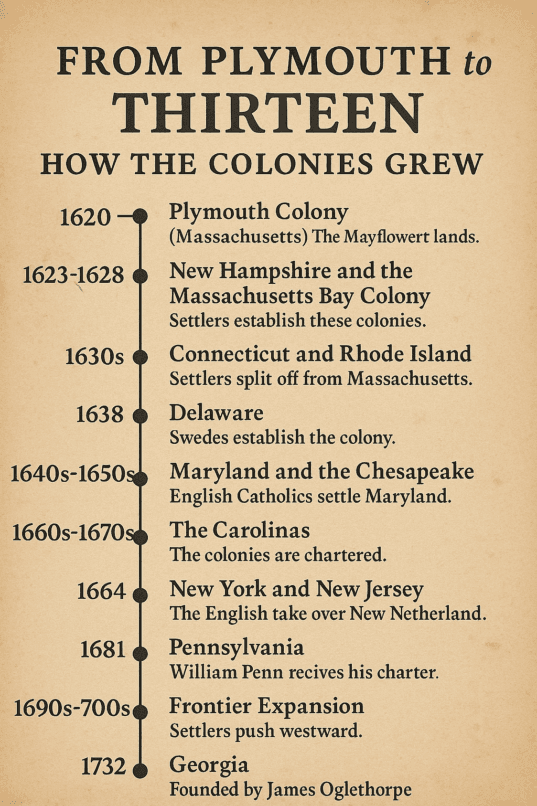

Before tea was dumped into Boston Harbor or musket fire echoed at Lexington and Concord, life in the American colonies pulsed with routine, ambition, and growing self-confidence. More than 150 years had passed since the earliest settlements at Jamestown and Plymouth. By the mid-1700s, Britain’s North American colonies flourished across varied landscapes and cultures, their growing prosperity quietly stitching together a shared identity that would soon defy the Crown.

From Frontier to Flourishing Society

The thirteen colonies stretched along the Atlantic coast, from the rocky shores of New England to the tidewater plantations of Georgia. Though all lived under British rule, each region developed its own character shaped by geography and purpose.

New England Colonies

(Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut)

Life revolved around tight-knit towns, church life, and hard work. Poor soil and long winters made large-scale farming difficult, so New Englanders turned to the sea — fishing, whaling, and shipbuilding. Local governments held town meetings, early exercises in democracy. Education was valued; Harvard College (1636) became the first institution of higher learning in the New World.

Middle Colonies

(New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware)

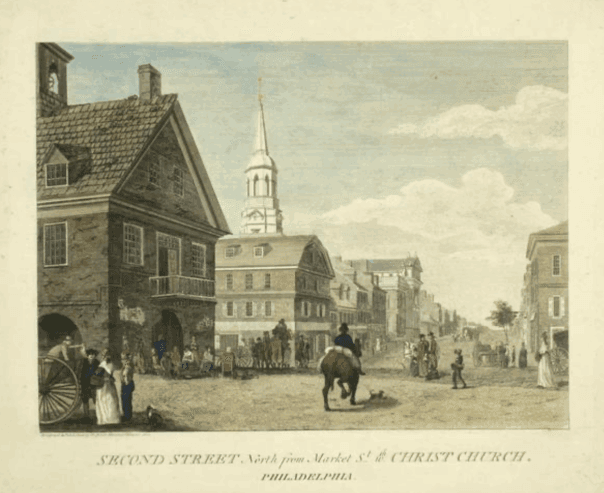

Fertile land and moderate climate created the “breadbasket” of the colonies. The ports of Philadelphia and New York thrived on shipping, printing, and commerce. Philadelphia , founded by William Penn as a “holy experiment” in tolerance , grew into the largest city in the colonies with nearly 25,000 residents by 1775, rivaling Boston in size and sophistication.

Southern Colonies

(Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia)

Warm weather and long growing seasons produced tobacco, rice, and indigo. Large plantations depended heavily on enslaved labor. Charleston became the South’s leading port; Virginia, the most populous colony, dominated politics, producing men like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry — whose fiery words, “Give me liberty, or give me death!”, would one day echo through the halls of revolution.

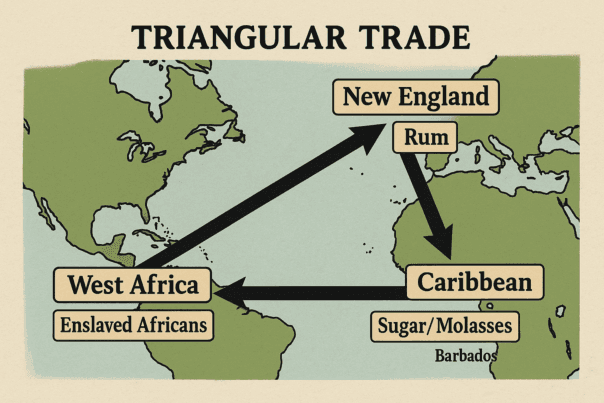

The Triangular Trade — Wealth and Human Suffering

Colonial prosperity rode the currents of the Atlantic trade system, often called the Triangular Trade. Ships from New England carried molasses from the Caribbean to distilleries in Boston or Newport, where it became rum. That rum was exchanged in West Africa for enslaved Africans, who endured the brutal Middle Passage to the Americas.

From Africa to the Caribbean and North America, goods, people, and profit flowed in a three-cornered loop. The trade enriched merchants and fueled shipyards, but it also tied the colonies into the cruelty of slavery. As the musical 1776 later reminded us, “Molasses to rum to slaves” — a refrain that laid bare the contradiction between liberty and bondage.

Prosperity and Inequality

Colonial society offered opportunity but was clearly divided by wealth and social standing. Most families lived modestly, their lives shaped by faith, family, and seasonal work. In northern towns, artisans crafted silver and fine furniture; in the southern colonies, enslaved Africans endured grueling labor on vast plantations. Women managed households and farms in their husbands’ absence but held few legal rights.

By mid-century, many colonists enjoyed higher living standards than their European counterparts: more land, more food, and a growing sense of independence. Still, they considered themselves proud subjects of the British Crown.

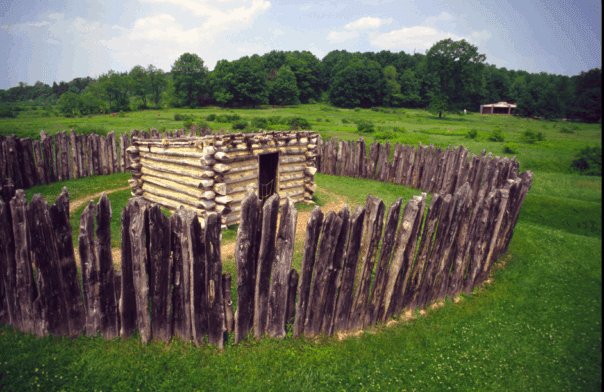

Clouds on the Horizon: The French and Indian War (1754–1763)

The colonies’ first encounter with large-scale warfare came during the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France.

A young George Washington, just twenty-two, led a Virginia militia into the contested Ohio River Valley. Eager and ambitious, he stumbled into a chain of misjudgments that sparked open conflict. His makeshift Fort Necessity fell after a brief siege, forcing his surrender — a humbling experience for the future commander of the Continental Army. Yet Washington learned from failure: the importance of discipline, clear communication, and respect for terrain. Those lessons would one day shape his success against Britain’s seasoned troops.

Britain ultimately triumphed, but victory came with enormous debt. To recover costs, Parliament turned to the colonies for revenue — a decision that would light the first sparks of rebellion.

The Road to Revolution Begins (1764–1775)

https://www.etsy.com/ie/listing/4328344791/colonial-williamsburg-sugar-cone-wm

1764 – The Sugar Act

Parliament imposed the first tax aimed at raising revenue directly from the colonies. Merchant James Otis denounced it, declaring, “Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

1765 – The Stamp Act

A tax on paper goods — from newspapers to legal documents — ignited boycotts and riots. Patrick Henry and Samuel Adams led protests, while the Sons of Liberty rallied crowds in Boston and beyond.

1766 – The Declaratory Act

After repealing the Stamp Act, Parliament asserted its full right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

1767 – The Townshend Acts

Taxes on glass, lead, paint, and tea revived boycotts. Colonial women, calling themselves Daughters of Liberty, wove homespun cloth to resist imported goods.

Across the colonies, taverns buzzed with debate, pamphlets circulated, and a shared identity began to form. The scattered provinces were learning to speak with one voice.

A Shared Awakening

By 1765, the colonies had evolved from fragile outposts to a string of prosperous societies spanning a thousand miles of coast. They differed in culture and economy but were increasingly united in spirit. The colonists still toasted the King, yet they began asking a dangerous question:

If we can govern ourselves here, why not entirely?

🎥 Experience the Mood of the Times

To step inside this turning point in history, watch the original movie that has been seen by millions of visitors over the years. Williamsburg: The Story of a Patriot is a landmark film created by Colonial Williamsburg in 1957. Filmed on location and starring a young Jack Lord (way before Hawaii Five-O) as a Virginia delegate torn between loyalty and liberty, it brings the debates, ideals, and tensions of the 1770s vividly to life. I know the film is vintage quality, but I still love it. Runs about 30 minutes.

Watch the full film here → click on the red letters.

Expanding Your Knowledge of Early America Leaders

⚜️ Do You Know? — William Penn (1644 – 1718)

Do you know that the statue on top of Philadelphia’s City Hall is William Penn, not Ben Franklin?

A Vision of Faith and Freedom

Born into privilege in London, William Penn was the well-educated son of Admiral Sir William Penn, a loyal servant of King Charles II. Yet instead of following his father’s path of military prestige and royal favor, the younger Penn shocked society by joining the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers — a group despised by England’s establishment for their radical belief in equality, pacifism, and the “inner light” within every soul.

Penn’s faith often brought him persecution and imprisonment, but it also shaped his vision for a new kind of society across the Atlantic. In 1681, the Crown granted him a vast tract of American land, a repayment of a royal debt owed to his father, and Penn named it Pennsylvania, meaning “Penn’s Woods.”

Building the City of Brotherly Love

Penn sought to create a “holy experiment,” a haven where religious freedom, representative government, and fair laws could coexist. He personally designed Philadelphia — the “City of Brotherly Love” — as a “green country town” of broad streets and public squares to encourage health, harmony, and community. His treaties with Native American tribes were grounded in fairness rather than conquest, an extraordinary approach for his time.

A Legacy That Endured

Under his guidance, Pennsylvania quickly became one of the most prosperous and tolerant colonies in North America, attracting settlers of many faiths. By the mid-1700s, Philadelphia had grown into a thriving hub of commerce, ideas, and innovation — home to thinkers, printers, and reformers like Benjamin Franklin who would help light the spark of revolution.

Penn’s ideals of liberty of conscience and just government echoed through the colonies, influencing both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution long after his death.

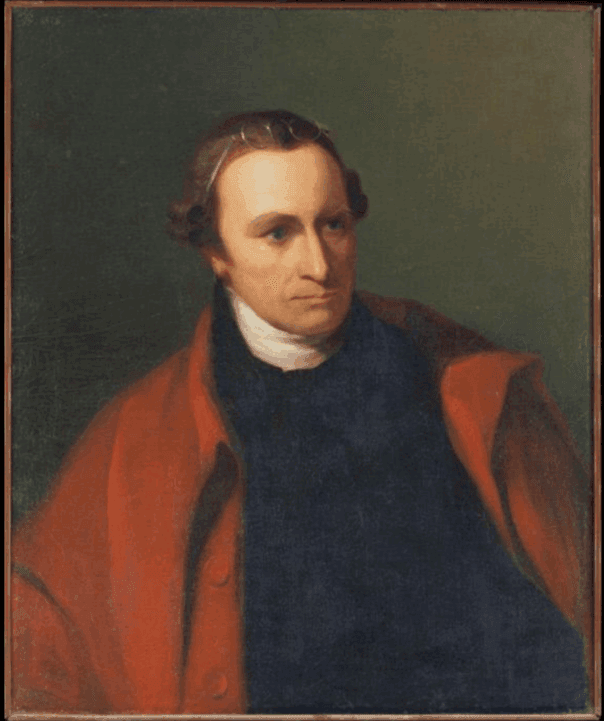

⚜️ Do You Know? — Patrick Henry (1736 – 1799)

Finding His Voice

Patrick Henry grew up on Virginia’s frontier, where self-reliance and honesty shaped his character. Though he first failed as a farmer and merchant, his natural gift for persuasion soon revealed itself in the courtroom. In 1763, as a young and relatively unknown lawyer, Henry argued the Parson’s Cause, defending colonial taxpayers against unjust British interference, and his fiery words captured the colony’s imagination.

The Voice of the Revolution

Just two years later, during the Stamp Act crisis, Henry burst onto the political stage with a speech that electrified the Virginia House of Burgesses. Drawing daring parallels between King George III and tyrants of the past, he declared, “Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third may profit by their example.” Gasps filled the chamber; some shouted “Treason!” but Henry stood undaunted.

When tensions with Britain reached a breaking point in 1775, Henry delivered his most famous oration at St. John’s Church in Richmond: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

Champion of Liberty

That declaration rallied Virginians to prepare for war and sealed Henry’s place in history as The Voice of the Revolution.He later served five terms as Virginia’s first post-colonial governor and remained a steadfast defender of individual liberty, warning against the dangers of centralized power.

Do You Know? — Roger Williams (1603 – 1683)

I grew up in Virginia, and don’t recall learning the story of Roger Williams . However in 2024, I made a visit to Providence, Rhode Island and heard about this often forgotten patriot.

A Radical Voice of Conscience

Born around 1603 in London, Roger Williams grew up during a time of fierce religious conflict. Trained at Cambridge University, he became a gifted linguist and theologian. Though ordained in the Church of England, Williams embraced Puritan ideals, seeking to purify worship and return to Scripture. But even among Puritans, he stood apart. He insisted that true faith must come freely, not by compulsion — a belief that would shape the future of American liberty.

Banishment and New Beginnings

Williams emigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631, hoping for a society built on spiritual integrity. Instead, he found the colony’s leaders enforcing religious uniformity. His sermons denounced civil interference in these matters and called for fair dealings with Native Americans, and alarmed authorities. In 1635, the General Court banished him for spreading “new and dangerous opinions.”

In the winter of 1636, he fled into the snowy wilderness, guided and sheltered by friendly Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes.

Founding Providence and a Legacy of Liberty

Williams settled along Narragansett Bay, purchased land, and named the settlement Providence, in gratitude for “God’s merciful providence,” and welcomed all who suffered “for conscience’ sake.”

In 1644, he secured a royal charter uniting Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick as the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, guaranteeing complete religious freedom and separation of church and state — a revolutionary idea that would not be fully realized in America until the First Amendment.

Beyond his political courage, Williams was a man of empathy and intellect. He mastered Native American languages and published A Key into the Language of America (1643), the first ethnographic study of Indigenous peoples in North America. He sought peaceful coexistence long before it became policy.

Roger Williams died in Providence in 1683, but his principles endured, influencing Jefferson, Madison, and generations of Americans who valued freedom of conscience. His colony, born from exile, became the model for a nation built on liberty of thought and belief — a reminder that sometimes the truest patriots are those who dare to dissent.

Looking Ahead

Next in the Bylandersea America 250 Series

🕯️ “The Spark: The Boston Protests and a World on the Edge of Revolution.”

I have no room in this post to include travel details, but stay tuned for future Bylandersea America 250 stories featuring Fredericksburg, Virginia, exploring George Washington’s Boyhood Home and other family sites, as well as visits to Patrick Henry’s homes, Scotchtown and Red Hill, in Virginia.