The “14th Colony”

My Bylandersea America 250 series explores the founding of the thirteen English colonies that ultimately banded together in revolution. Yet there is an older settlement that doesn’t fit neatly into that English storyline: St. Augustine, Florida. In the Revolutionary era, Florida was sometimes described as a “fourteenth colony,” governed as East and West Florida, though it remained loyal to the Crown. Because I once called St. Augustine home, I want to share the story of its founding before we continue along the road to the Revolution.

Founded in 1565, decades before Jamestown (1607) or Plymouth (1620), St. Augustine stood as the capital of Spanish La Florida for more than 200 years. Though it never became part of Britain’s rebellious colonies, its history is inseparable from the broader American story. St. Augustine became, in effect, a “fourteenth colony” — a European outpost shaped by empire, faith, Indigenous encounters, African labor, and Mediterranean immigrants.

Its survival against attack, its blend of cultures, and its passage through Spanish, British, and eventually American hands add depth to our understanding of early America. To tell the story of this “14th colony” is to venture beyond the English Atlantic and see the wider world that became the United States.

Founding and First Years

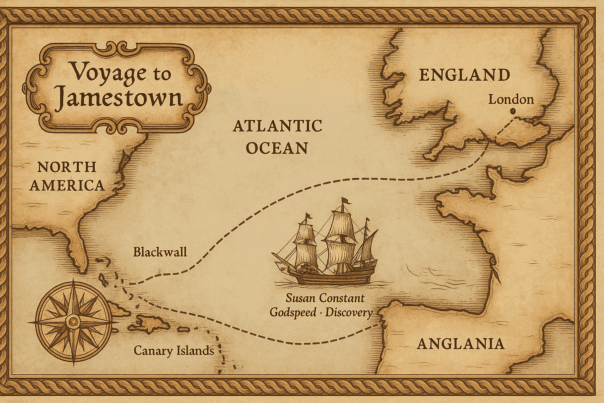

When Spanish Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés sailed into Florida’s northeastern coast in 1565, he carried orders to protect Spain’s treasure fleets, spread Catholic faith, and secure Spain’s claim to “La Florida.”

On September 8, the Feast Day of St. Augustine, Menéndez came ashore. A Mass was celebrated, marking what many consider the first Catholic ceremony in what is now the continental United States. The new settlement was named in honor of St. Augustine of Hippo.

From the beginning, life was precarious. The Spanish ousted French settlers at nearby Fort Caroline (now Jacksonville, FL) in a bloody conflict remembered at Matanzas Inlet, while struggling against the subtropical climate and negotiating tense relations with the Timucua people. Despite challenges, St. Augustine endured, laying the foundation for centuries of continuous occupation.

Ponce de León & the Search for La Florida

Long before St. Augustine was founded, Juan Ponce de León made history by becoming the first known European to set foot on the Florida peninsula in 1513. (Yes, that far back.) Sailing north from Puerto Rico, he named the land La Florida—“land of flowers”—because he arrived during the Easter season.

Ponce de León is often linked to the legend of the Fountain of Youth, though this tale grew more in folklore than fact. What mattered most was Spain’s claim: his exploration planted the Spanish flag nearly a century before the Pilgrims ever landed at Plymouth.

By the time Pedro Menéndez arrived in 1565, Spain was fulfilling Ponce de León’s first vision: establishing a permanent foothold in Florida that would anchor Spanish power for centuries.

Castillo de San Marcos & Defensive Evolution

The Castillo de San Marcos or fort became the base of St. Augustine’s survival. Construction began in 1672 after wooden forts failed against enemy attacks. Built of coquina stone, a shell-limestone composite, the walls absorbed cannon fire rather than shattering, proving nearly indestructible.

Over time, the fort expanded and adapted to changing warfare. Thanks to its strength, St. Augustine served as the military, administrative, and religious capital of Spanish Florida for more than two centuries.

Missions, Society & Culture

While the city often appears in military history, it was also a center of religion, trade, and culture. Spanish friars built missions to convert Indigenous peoples, producing cultural blending.

The community was diverse: Spanish officials, soldiers, Franciscan friars, enslaved Africans, and free people of African descent all shaped daily life. Archaeology reveals their diet, crafts, and ties to the broader Spanish Caribbean. Though fires destroyed many early buildings, St. Augustine’s colonial identity remains vivid.

🇬🇧 British Rule & The Minorcan Story

In 1763, Spain ceded Florida to Britain after the Seven Years’ War. St. Augustine became the capital of British East Florida, a lesser-known but significant chapter.

During this period, Dr. Andrew Turnbull recruited more than 1,400 Mediterranean laborers, primarily from the island of Menorca, along with Greeks, Italians, and Corsicans to establish the colony of New Smyrna. Harsh conditions, hunger, and disease decimated the group. In 1777, about 600 survivors marched to St. Augustine, where they were granted refuge.

The Minorcans became an enduring community within the city, leaving additional cultural legacies still seen today in sites like the St. Photios Greek Orthodox Shrine and in beloved local dishes such as Menorcan clam chowder spiced with datil peppers.

🇪🇸 Spanish Return & American Transition

Spain regained Florida in 1783, but the era was brief. By the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 (ratified 1821), Spain ceded Florida to the United States. St. Augustine briefly served as the territorial capital before government functions moved to Tallahassee.

Thus, St. Augustine’s story is not simply “Spanish then American.” It passed through multiple empires and cultures, each leaving lasting imprints in its architecture, traditions, and memory.

Why St. Augustine Matters in the 250-Year Narrative

- Predates Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620) by decades.

- Endured wars, raids, and shifting empires.

- Highlights the contributions of Spanish, Indigenous, African, and Minorcan peoples in shaping early America.

St. Augustine reminds us that America’s beginnings extend beyond the English colonies, offering a more complex and inclusive story of origins.

Do You Know: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Few names loom larger in St. Augustine’s history than Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. Born in 1519 in Asturias, Spain, Menéndez rose from a seafaring family to become a skilled naval officer. In 1565, King Philip II of Spain appointed him Adelantado of Florida, charging him with colonizing and defending Spain’s claims.

Menéndez not only founded St. Augustine but also orchestrated Spain’s victory over the French at nearby Fort Caroline, securing La Florida for the Spanish Crown. Fierce, determined, and devout, he combined military skill with religious zeal. Though often remembered for ruthless actions against the French Huguenots, his leadership allowed St. Augustine to survive when many other early colonies failed.

Menéndez died in 1574, but his vision left behind the enduring settlement we know today as America’s oldest city.

Touring Colonial-Era St. Augustine

Castillo de San Marcos

No visit to St. Augustine is complete without exploring the Castillo de San Marcos, the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States. Constructed of resilient coquina stone in the late 1600s, the fortress has withstood sieges, hurricanes, and centuries of change. Today, visitors can climb its ramparts, gaze across the Matanzas Bay, and imagine watchmen scanning the horizon for enemy ships. National Park rangers and reenactors bring the site alive with musket drills and booming cannon demonstrations, a vivid reminder of the strategic importance this stronghold once held for the Spanish Empire.

Colonial Quarter

The Colonial Quarter is an immersive living history museum where the centuries peel back one layer at a time. Here, costumed interpreters guide visitors through reconstructed streets and workshops representing the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. You can watch a blacksmith hammer out iron, see a musket drill performed, and climb a 35-foot wooden watchtower overlooking St. George Street. It’s an ideal stop for families, as hands-on exhibits and storytelling create a sense of daily life in colonial St. Augustine.

Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine

Located in the heart of downtown, the Cathedral Basilica is the oldest parish church in the United States. Its coquina walls and Spanish Colonial design reflect the city’s heritage, while stained-glass windows and ornate altars provide a sense of timeless beauty. The original parish was founded in 1565, though the current structure was completed in the late 18th century after fire destroyed earlier churches. Whether you’re attending Mass or simply admiring the art and architecture, the Basilica embodies St. Augustine’s enduring spiritual and cultural legacy.

Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park

The Fountain of Youth Archeological Park is an attraction that blends legend with authentic history. Long associated with Ponce de León’s mythical search for eternal youth, the site today highlights the archaeological remains of St. Augustine’s earliest settlement area. Visitors can sip from the famous spring, explore a recreated Timucua village, and walk through exhibits about Spanish missions and Native American life. Daily cannon firings and peacocks strutting the grounds add to the colorful atmosphere, making the park equal parts education and entertainment. (Although I tried many times, unfortunately, the Fountain of Youth failed me. )

Chapel of Our Lady of La Leche and Mission Grounds

North of downtown, the Mission Nombre de Dios and Chapel of Our Lady of La Leche mark the very site where Spanish settlers celebrated the first Catholic Mass in 1565. The tiny chapel, America’s oldest Marian shrine, draws pilgrims seeking blessings of fertility and family. Rising nearby is the striking 208-foot stainless-steel Great Cross, a landmark visible across the city. The expansive grounds are also home to Founder’s Day celebrations each September, commemorating Pedro Menéndez’s landing and the first Mass with reenactments, liturgy, and festivities that honor St. Augustine’s sacred beginnings.

Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse & Historic Streets

Walking along St. George Street, the city’s historic thoroughfare, feels like stepping into another century. Among the preserved colonial-era structures is the Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse, a humble red cedar and cypress building dating back to the early 18th century. Inside, exhibits show what education looked like in colonial Florida. Along the way, boutiques, cafés, and museums housed in centuries-old buildings invite visitors to pause and imagine the bustling life of the town’s earliest inhabitants.

Fort Matanzas National Monument

About 14 miles south of downtown, Fort Matanzas, now a National Monument, guarded the southern approach to St. Augustine from the mid-18th century. Built by the Spanish in 1742, the small coquina watchtower played an outsized role in defending the city from British incursions. Today, visitors can enjoy a short ferry ride across the Matanzas River to explore the fort, walk the nature trails, and learn about the vital role this outpost played in the survival of colonial St. Augustine.

Practical Tips for Visiting St. Augustine

Best Time to Visit: Fall and spring bring pleasant weather and fewer crowds; summer can be hot and humid.

Getting Around: The Old Town Trolley Tour offers convenient hop-on, hop-off stops at all the major colonial sites.

Passes & Tickets: Consider a combination ticket for the Colonial Quarter, Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse, and Fountain of Youth to maximize value.

Don’t Miss: Sunset views from the seawall near the Castillo, and tasting Menorcan clam chowder at a local café.

And that’s not all.

Beyond its colonial roots, St. Augustine invites visitors to keep peeling back the layers of history and culture. You can step into the elegance of the Gilded Age at Henry Flagler’s grand hotels, follow the Civil Rights Trail through sites of pivotal 1960s marches and protests, or return in winter for the dazzling Nights of Lights festival that blankets the city in holiday magic. Food lovers will also find plenty to savor, from fresh seafood and farm-to-table dining to the signature flavors of Minorcan chowder. St. Augustine is not only America’s oldest city — it’s a destination that continues to reinvent itself while honoring every era of its story.

For more information: FloridasHistoricCoast.com